Constitutional Defences

In 1985, the Supreme Court of Canada considered the B.C. Motor Vehicle Reference case(Reference Re Section 94(2) of the Motor vehicle Act (1985) 2 SCR 486). It found that the law created an absolute liability offence, and that imprisonment was a possible penalty. The court ruled that such a combination is unconstitutional (a violation of s. 7 of the Charter), and required every other court that encounters such a defect in a law should strike that law down.

CC s. 91 is such a law, and every court is supposed to strike it down if the government tries to use it. CC ss. 92, 93, 94, 95, and 97 also exhibit this defect in some circumstances.

If the reader is dealing with a CC s. 92, 93, 94, 95, or 97 or FA s. 112 case, each argument below should be tested by substituting the charge identification for CC s. 91. In many of the cases, the argument will still apply.

In 1988, the Supreme Court of Canada considered the Morgentaler et al v. The Queen and the Attorney General of Canada case ([1988] 1 SCR 30). It found that the government had provided a specifically-tailored defence to that particular [criminal] charge in the law. The Court also found that the defence was illusory, or so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory. The Court ruled that when a court is asked to consider a case that exhibits that defect in the law, it must strike the defective law down.

CC s. 91 exhibits that defect, as do CC ss. 92, 93, 94, 95, and 97 in some circumstances.

In 1991, the Supreme Court of Canada considered the Wholesale Travel case ([1991] 3 SCR 154) to settle the validity of strict liability offences. In the case of a ‘regulatory offence’ or a ‘public welfare offence’, including those that carry the penalty of imprisonment, fundamental justice does not require that mens rea be an element of the offence. Fundamental justice is satisfied if there is a defence of reasonable care, and the burden of proving reasonable care (to the civil standard) may be cast on the defendant. In the case of ‘true crimes’, however, fundamental justice requires that mens rea be an element of the offence, and the burden of proving mens rea (to the criminal standard) would have to would have to be on the Crown [emphasis added].

CC s. 91 is a law that does not deal with a regulatory offence. It deals with a ‘true crime,’ and therefore the government must prove mens rea. CC s. 91 is designed and written to permit the conviction and imprisonment of an accused without the Crown having to prove mens rea, and such a law must therefore be struck down by any court that is asked to consider it.

A licence is defined in law as a document used in regulatory law to give permission for a person to engage in regulated activities that would otherwise be unlawful.

A licence apparently cannot be used in criminal law to give permission for a person to engage in criminal activity, because the government has no known power to licence individuals to commit crimes. In the light of the Morgentaler decision, the Supreme Court of Canada apparently does condone the issuance of a document that is “a specifically-tailored defence to a particular [criminal] charge” – but is not a licence to commit that crime.

If the government can licence an individual to commit the crime of possessing a firearm, there is no apparent reason why it cannot licence another individual to commit the crimes of rape, robbery and murder.

DETAILED GENERAL ARGUMENTS

Many charges made under Criminal Code firearms control provisions are vulnerable to a challenge under s. 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

FUNDAMENTAL JUSTICE CONSIDERATIONS

As Hogg says in his Constitutional Law of Canada, the dividing lines between “strict liability” offences, “absolute liability” offences and “true crime” offences (“offences of mens rea”) are ill-defined and shaky. He says, in his 44.11, that an absolute liability offence consists “simply of doing the prohibited act. There is no requirement of fault, either mens rea or negligence. The defendant could be convicted even if he or she had no intention of breaking the law and also exercised reasonable care to avoid doing so.”

He also defines a strict liability offence, which “again consists simply of doing the prohibited act; however, it is a defence if the defendant proves to the civil standard of the balance of possibilities that he or she exercised reasonable care to avoid committing the offence.” There is, however, a fault requirement of demonstrable negligence, and only an accused who did not exercise reasonable care is liable.

In the R. v. Wholesale Travel case ([1991] 3 SCR 154), the Supreme Court of Canada said that the offence was not a “true crime,” but was merely a “regulatory offence” or “public welfare offence.” (It would appear that Canada’s Parliament is precluded by the Constitution from enacting regulatory law in the firearm area, and that all firearms control laws enacted by Bill C-68, as amended, are criminal law.) The SCC ruled, in that case, that a regulatory offence did not imply moral blameworthiness, and attracted less social stigma. That is apparently a key point in analyzing federal firearms control laws. The Court treated it as obvious that the offence of misleading advertising fell into the “regulatory” category, despite the fact that it carried a maximum penalty of five years’ imprisonment–quite a stretch for doing something that did not imply moral blameworthiness and “attracted little social stigma”!

The Supreme Court of Canada apparently likes to consider radical constitutional results as being able to be based on findings of stigma levels, although there is apparently never any evidence on that point. Is the stigma attaching to a particular offence unknown and perhaps unknowable? Hogg apparently thought so, because it would depend upon such a host of circumstances related to both the offence and the offender, and would vary according to the eye of the beholder. The concept is apparently too uncertain to warrant constitutional consequence of any kind. Perhaps it would be preferable to use the presence of the penalty of imprisonment as the dividing line between those offences that require mens rea and those that require only negligence.

Hogg also said, in 44.11, that the Competition Act contained a “reverse onus” clause. That clause required the defendant to prove, on the balance of probabilities, that he had exercised reasonable care to avoid making false or misleading claims. The effect of the Sault Ste. Marie decision ([1978] 2 SCR 1299, 1325-36) was that a regulatory offence was to be regarded as one of strict liability. Two characteristics of strict liability were (1) that there was a defence of reasonable care, and (2) that the burden of proving reasonable care rested on the defendant. That would be true even if the Act had been silent as to the defence and the burden of proof. Therefore, in order to uphold the offence in Wholesale Travel (or any other strict liability offence involving imprisonment), the Court also had to decide whether the reverse onus was defeated by the Charter of Rights, not by s. 7 but by s. 11(d). S. 11(d) is the presumption of innocence clause. The Court, by a five to four majority, upheld the reverse onus–but in a case that was identified as involving only regulatory law.

Hogg apparently considered that the effect of the Wholesale Travel case was to settle the validity of strict liability R. v. Martin ([1992] 1 SCR 838) and R. v. Ellis-Don ([1992] 1 SCR 840). He considered that for a “regulatory offence” or “public welfare offence,” including those that carry the penalty of imprisonment, fundamental justice did not require that mens rea be an element of the offence. Fundamental justice would be satisfied if a defence of reasonable care could succeed, and the burden of proving reasonable care (to the civil standard) could be cast on the defendant.

In the case of “true crimes,” however, Hogg considered that fundamental justice required mens rea be an element of the offence, with the burden of proving mens rea (to the criminal standard) on the Crown. The distinction between “true crimes” and “regulatory offences” (“public welfare offences”) seems to depend on vague notions of moral blameworthiness and social stigma, not upon objective considerations. The seventy of the penalty seems to be irrelevant, in the opinion of the Court. The offence in the Wholesale Travel case carried a penalty of up to five years’ imprisonment; but it was still classified as a regulatory offence.

Hogg wrote that the effect of the B.C. Motor Vehicle Reference ([1985] 2 SCR 486) was to outlaw absolute liability for all offences carrying the penalty of imprisonment. Fundamental justice required that the offence include an element of fault, either mens rea (if the offence is a true crime) or negligence (if the offence is a “regulatory offence”). In his opinion, it is the absence of an element of fault that causes absolute liability to violate s.7, and s.7 has no application to an offence where penalty is a fine, even a very large fine, because “liberty” is not affected.

Now, let us analyze Hogg’s views in the light of the distinctions made between an “absolute liability” offence, a “strict liability” offence, and a “true crime” or “mens rea” offence.

Hogg says, “The Supreme Court of Canada in Wholesale Travel was unanimous in its view that the offence of false or misleading advertising in the Competition Act was not a ‘true crime,’ but was merely a ‘regulatory offence’ or ‘public welfare offence’.” Cory J. explained that the characteristic of a “true crime” was that “inherently wrongful conduct” was punished.

“Inherently wrongful conduct” is the commission of a malum in se–an act that is evil–an act, that under almost any circumstances would be morally blameworthy. In contrast, regulatory law is designed to regulate the ways in which people behave, and a regulatory offence is the commission of a malum prohibitum. In that case, the offence would not be an offence if some bit of regulatory law did not prohibit it; it would be normal behavior.

A regulatory offence was designed to establish standards of conduct for activity that could be harmful to others; it did not imply moral blameworthiness; and it attracted less social stigma [emphasis added]. Therefore, the Court reasoned, it was not a constitutional objection to the offence that it was premised on negligence rather than mens rea.”

Does violating a particular CC or FA firearms section constitute a “true crime,” or is it merely a “regulatory offence” that attracts “less social stigma”? Or is it possibly a prohibited “absolute liability” offence with the possibility of imprisonment that requires consideration of section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms?

- Each firearms offence is embedded in the Criminal Code, which deals with criminal prosecutions for true crimes, not with regulatory offences.

- Regulatory offences do not saddle the ‘criminal’ with a criminal record.

- A person convicted of any sort of firearms offence is almost certainly going to have a prohibition order imposed upon him or her, forbidding him or her to possess firearms and other items. That is a severe social stigma, as it brands the person as a danger to society, unworthy of trust, and likely to use firearms for violence if granted access to them.

- A person convicted of violating such a provision gets a criminal record for committing a firearms offence, which affects his life and livelihood from that day forward, and is a severe social stigma.

- A person with a criminal record is at a severe disadvantage when applying for a position, and that criminal record is a severe social stigma that may prevent him or her from being seriously considered for the position.

- A person with a criminal record for violating a firearms control provision cannot be bonded, and that is a severe social stigma that often limits the person’s attempts to earn a livelihood.

- A person with a criminal record–particularly one for having committed a ‘firearms offence’ –will usually be denied entry into any nation outside Canada because of that record, and that is another severe social stigma.

Clearly, a violation of a CC or FA firearms control provision is quite unlike the Wholesale Travel case. Instead of a violation of a regulatory Act, the offence is a violation of the Criminal Code. There was no possibility that Wholesale Travel or any individual employed by Wholesale Travel would be saddled with a criminal record, or be saddled with a prohibition order, two severe social stigmas that are automatically applied to a violator of, for example, CC s. 91(1).

Hogg goes on to say, “The effect of the Wholesale Travel case is to settle the validity of strict liability [99]. In the case of a ‘regulatory offence‘ or a ‘public welfare offence‘, including those that carry the penalty of imprisonment, fundamental justice does not require that mens rea be an element of the offence. Fundamental justice is satisfied if there is a defence of reasonable care, and the burden of proving reasonable care (to the civil standard) may be cast on the defendant. In the case of ‘true crimes‘, however, fundamental justice requires that mens rea be an element of the offence, and the burden of proving mens rea (to the criminal standard) would have to would have to be on the Crown[emphasis added].”

With all due respect to Mr. Hogg, it is far from clear that, ” The effect of the Wholesale Travel case is to settle the validity of strict liability.” Certainly, it can settle the standard by which a “strict liability” offence should be judged (negligence versus mens rea), but it is far from settling which particular offences are strict liability offences, and which are true crime/mens rea offences.

Is a CC or FA firearms control offence, then, a criminal offence or a regulatory offence? At first glance, it would appear that an argument could be made that it is a regulatory offence. However, as Hogg says, ” A regulatory offence, on the other hand, was designed to establish standards of conduct for activity that could be harmful to others; it did not imply moral blameworthiness; and it attracted less social stigma [emphasis added].”

It is clear that conviction for a violation of a CC or FA firearms control provision does inflict a severe social stigma. Because the offence is laid out in the Criminal Code, conviction therefore will inflict a criminal record for a firearms crime on the accused (whether or not a punishment of imprisonment is imposed, as it may be).

That criminal record will dog the convicted individual far into the future, probably making it impossible for him to earn a livelihood in any position that requires him to be bonded, or to leave Canada on business. It can also prevent him from even visiting any other country for any purpose whatever, another severe social stigma. It will also be a severe “social stigma” disadvantage every time he applies for a position or runs for office.

Additionally, the Crown usually adds an application for a prohibition order to each and every firearms-related charge–no matter how petty or insignificant, and no matter whether or not the charge has anything to do with violence.

The social stigma of such a prohibition is severe. It declares to the world that the individual subjected to it is seen as a menace to society who must be kept away from weapons. That is a severe social stigma, appropriate to a person convicted of a ‘true crime.’ It is the sort of long-term social stigma that one would not expect to see imposed as a result of conviction for a mere regulatory offence. One does not prohibit a driver to possess an automobile because he was found guilty of speeding, for example.

If the court convicts an accused of a CC or FA firearms control offence, every firearm possessed by the accused that has been “seized and detained” is automatically forfeit to the Crown, whether it was involved in the offence or not [CC s. 491(1)(b)]. The court has no jurisdiction to alter that, regardless of the particular circumstances of the case.

That is an extra penalty, which also declares to the world that the individual subjected to it is seen as a menace to society who must be kept away from weapons. That imposes a social stigma that might be appropriate to a person convicted of a ‘true crime’–but is not a social stigma that one would be imposed as a result of conviction for a mere regulatory offence. A person found guilty of speeding does not have his automobile confiscated, for example.

It is the habit of the police to seize all firearms (and often, all related materials) of the accused at the beginning of an incident. CC s. 491(1)(b), therefore, usually results in the all of those goods being forfeited to the Crown. That is often unjustifiable, but it is forced by the letter of the law.

CC s. 491(1)(b), by taking discretion away from the court, tends to bring the law into disrepute every time some minor error of paperwork results in the loss and destruction of an expensive and important firearms collection or a life-long hunter’s battery of firearms.

That sort of forfeiture to the Crown is a social stigma that separates the accused from others. Others are allowed to own such property, but the accused has all of his firearms-related property confiscated by the state–which apparently regards him or her as a menace to society.

Conviction of a CC or FA firearms control offence imposes a criminal record on the accused, which will almost certainly bar him from earning a livelihood in any endeavor requiring that he be bonded. He is branded as a dishonest felon who cannot be trusted. He is, from that day forward, assumed to be a dishonest person who cannot be trusted with money or property.

That same criminal record for a CC or FA firearms offence can and probably will bar him from entering other countries, and restrict his life and livelihoods to things he can do without leaving Canada. The criminal record will brand him as a person who is such a menace to society that no other country is likely to admit him within its borders, if it is aware of his criminal record, and that is a severe social stigma.

Had Parliament intended CC and FA firearms control offences to be a regulatory offences, it would have allowed the provinces to put them into regulatory law, rather itself putting them into criminal law. The offences are all, therefore, criminal offences.

Even if Parliament had placed them in the Firearms Act, the social stigma is identical. A criminal record and, almost always, a prohibition order–the stigmas are the same. That is because the Firearms Act is criminal law, not regulatory law. Parliament has no authority to enact regulatory law regarding firearms, so it was forced to use its criminal law powers.

Considering all of those factors, it seems clear that CC or FA firearms control offences are not, and cannot possibly be considered to be, “regulatory offences.” They are severe criminal offences, carrying penalties of years in prison and imposing severe social stigmas–and that is exactly what Parliament intended them to be.

Therefore, each CC or FA firearms control offence is a criminal offence, treated by the justice system as a “true crime,” and proof of mens rea is required. It is not a “strict liability regulatory offence.”

Hogg says, “The effect of the B.C. Motor Vehicle Reference is to outlaw absolute liability for those offences that carry the penalty of imprisonment. Fundamental justice requires that the offence include an element of fault, either mens rea (if the offence is a true crime) or negligence (if the offence is a ‘regulatory offence’). It is the absence of any element of fault that causes absolute liability to violate s.7 [of the Charter]. Of course, s.7 has no application to an offence that carries only the penalty of a fine, even a very large fine, because in that case ‘liberty’ is not affected. Therefore, so long as no sentence of imprisonment is provided for, it is still possible for the Parliament or Legislatures to create offences of absolute liability.”

CC or FA firearms control offences have, in most cases, precisely the potential that the Supreme Court of Canada found offensive in the B.C. Motor Vehicle Reference. In that case, Reference Re Section 94(2) of the Motor vehicle Act (1985) 2 SCR 486, the Court ruled:

“A law that has the potential to convict a person who has not really done anything wrong offends the principles of fundamental justice, and, if imprisonment is available as a penalty, such a law then violates a person’s right to liberty under s. 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [emphasis added].” (492)

Before preparing a defence against a charge made under a CC or FA firearms control provision, it is necessary to determine:

- Is the offence an “absolute liability” offence that has “the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong”? The exact wording of the provision should determine that.

- Is the offence a “strict liability” offence that offers a defence of due diligence and does not impose a severe social stigma on the accused if he is convicted? If there is no hint that a defence of due diligence is relevant, it may well be an “absolute liability” offence with the potential of taking away the liberty of the accused, and that would be unconstitutional.

- Is the offence one that does impose a severe social stigma on the accused, if convicted? If it is, Parliament obviously intended it to be seen as a “true crime” offence–and that means that the Crown must prove mens rea, and the facts–beyond a reasonable doubt.

- Does the offence require that the Crown prove mens rea? Or mere negligence?

It is quite important to decide what type of offence the offence is–absolute liability, strict liability, regulatory offence or true crime–before beginning preparation of the defence.

It is also necessary to realize that the judge may not agree with the defence lawyer’s estimate of which categories the offence falls into, and therefore fallback positions should be prepared in case of adverse decisions by the judge. Fortunately, several are available.

Has a particular CC or FA firearms control offence “the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong”?

Let us consider an example.

Has CC s. 91(1) “the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong”?

It apparently does. Many, many firearms control cases have to be dealt with by accused people who cannot afford a lawyer. When they read CC s. 91(1), it contains no indication whatever as to whether the accused should consider it to be a normal criminal offence, requiring the Crown to prove mens rea, or a “regulatory offence” where a defence of due diligence might save the accused from conviction. There is no indication in the section, anywhere, that a defence of due diligence may be relevant in any way.

Hogg says, of the Wholesale Travel case, that “The Act made clear that there was no requirement of mens rea: the only defence was one of reasonable care, and the burden of proving reasonable care rested with the accused.”

That is certainly not the case with CC s. 91. It contains no indication whatever that Parliament had any such intent. It lists defences [in s. 91(4) and (5)], but due diligence is not among them.

CC s. 91(1) is, in wording and appearance, an absolute liability offence–and that perception is augmented by the fact that it is prosecuted with a reverse onus requirement set by CC s. 117.11:

- 117.11 Where, in any proceedings for an offence under any of sections 89, 90, 91, 93, 97, 101, 104 and 105, any question arises as to whether a person is the holder of an authorization, a licence or a registration certificate, the onus is on the accused to prove that the person is the holder of the authorization, licence or registration certificate.

It should be carefully noted that CC s. 117.11 does not apply the reverse onus to CC s. 92 (or 94, 95, or 97), possession knowing that the person is not the holder of a licence or registration certificate under which he may possess it.

Where CC s. 117.11 does not impose a reverse onus, the onus is on the Crown to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the accused is not the holder of the licencing document. Given the poor quality of the records created by and held in the files and computers of firearms control officials, that can be very difficult–especially because it requires proving a negative.

For example, a simple misspelling of a name can make computer search of valid licences result in the information that the accused has no licence, although he in fact is the holder of a licence, but with his name misspelled as “MacDonald” when it is actually “MacDoneld.”

The licence held by an accused is a simple piece of paper, vulnerable to all the dangers that result in the loss or destruction of pieces of paper. Loss of such a piece of paper does not mean that the accused is no longer the holder of a licence–it may merely mean that the paper was inadvertently put through the cycles of a washing machine in the pocket of her shirt. The possibility of such accidents makes reverse onus unreasonable.

It is therefore quite important to force the Crown to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the accused was not the holder of a licencing document, where that document is a “specifically tailored defence to a particular charge.” That is related to the Therapeutic Abortion Certificate that featured in the Morgentaler case [Morgentaler et. Al. V. the Queen and the Attorney General of Canada (1988) 1 SCR 30].

The very similar FA s. 112(1) criminal charge is subject to FA s. 112(4):

- 112 (4) Where, in any proceedings for an offence under this section, any question arises as to whether a person is the holder of a registration certificate, the onus is on the defendant to prove that the person is the holder of the registration certificate.

The reverse onus imposed by CC s. 117.11 or FA s. 112(4) increases the potential of CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112 “to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong.”

It would appear that the reverse onus is, therefore, an improper and possibly unconstitutional device, apparently designed to void the accused’s right to stay out of the witness box, to make convictions easier for the Crown, and to ease the workload of the Crown. CC s. 117.11 and FA s. 112(4) therefore tend to bring the law into disrepute, as do CC s. 91(1) and (2), and FA s. 112(1).

The Crown has spent hundreds of millions of dollars in public funds to create and administer the authorization, licence, registration certificate, and other licencing document systems. The Crown has enormous resources, voluminous files, and extensive records (in computers and in files), administered by large numbers of Crown employees paid from the public purse.

The reverse onus, therefore, tends to bring the law into disrepute because those records exist.

The records are public property, and public employees have exclusive access to them–but the law does not require the Crown to make any effort whatever to find the records that may prove the innocence of the accused. Such records may very well actually be in the Crown’s huge and very expensive system–but the entire burden of proof that they exist is put upon the accused, who has no access to that data base.

Additionally, the data base itself is riddled with errors, omissions and duplications. Searching it is difficult, and often the document sought is actually in there–but cannot be found by the searcher. In a spectacular demonstration of that, two documents were entered as “evidence” in the trial of Douglas Anderson, in 1988. One stated:

- I have made a careful examination and search of such records and have been unable to find any record of a valid registration certificate having been issued for a CHINESE MACHINE GUN, Calibre 9mm, Serial Number 001120.

The second document was a photocopy of a registration certificate, with this information added:

- CERTIFIED TO BE A TRUE COPY OF THE ORIGINAL TO WHICH IT PURPORTS TO BE A TRUE COPY OF

The firearm is described, on the registration certificate, as:

- Make: CHINESE (“Chinese” is the nationality of a people, not a maker of firearms.)

- Model: M3A1 (It was actually a Model 36, which is a Chinese copy of a US M3A1.)

- Type: HG (“HG” means handgun; it should have been “SM” for submachine gun.)

- Calibre: .45 (It was .45 calibre; the “9mm” in the other paper was a Crown error.)

- Serial number: 001120 (That was the correct Serial number, as on the other paper.)

Both documents refer to the same firearm. Both were created specifically for use in court. Both were signed by Ronald Knowles, then head of the Firearms Registration Administration Section of the RCMP. Both were signed on the same day.

Given the subtlety and complexity of the legal arguments surrounding “strict liability”, “absolute liability”, “true crimes”, “mens rea” and “regulatory offences”–issues that often confuse lawyers–a person without counsel is very likely to be unable to either understand or deal with the legal puzzles involved. Indeed, even lawyers and judges have been known to misunderstand the effects of law affected by those terms, and to make mistakes about which of those ill-defined areas of law is being dealt with in a particular case.

The likelihood that the accused will plead guilty when he is not guilty is very high. That fact alone strongly increases the obvious potential in s. 91(1) to imprison a person who has not really done anything wrong. That, in turn, tends to bring the law into disrepute.

The fact that there is no indication whatever in CC s. 91 that a defence of due diligence would be relevant is evidence that Parliament did not consider a defence of due diligence to be relevant when a person is charged with violating s. 91(1). Parliament thereby demonstrated that it considered violation of s. 91(1) to be a ‘true crime,” in the form of a criminal offence.

Is it possible for a person to violate s. 91(1) “without doing anything wrong”? It certainly is.

- A person may not notice that his licence is about to lapse, or may not notice that his registration certificate is about to lapse [see FA s. 127(2)(b)]. If either of those two documents lapses, the person may fall into violation of CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) without any act on his part. Mere inattention, without an act, should not be sufficient justification for imprisoning the accused–so CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) clearly “has the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong [emphasis added].”

- A Chief Firearms Officer is authorized to revoke any licence “for any good and sufficient reason” [FA s. 70(1)], and the Registrar may revoke a registration certificate “for any good and sufficient reason” [FA s. 71(1)(a)]. Either of them may revoke a licencing document without any valid evidence of wrongdoing by the holder of the document. If either of those two documents is revoked, and the required notification to the person miscarries, the person may fall into violation of CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112 without any act on his part, and without any wrongdoing on his part. Revocation without proof of notification should not be sufficient justification for imprisoning the accused–so CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) clearly “has the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong [emphasis added].”

- Where a licencing document is revoked under FA s. 70 or 71, s. 72(1) requires notification to be sent to the holder–but it is not unknown for such a notification to miscarry. It is also not unknown for the notification to arrive when an accused who is a military person was out of the country on duty for an extended period, or an accused who works in wilderness areas was away on an extended stay in the wilderness, or an accused who was taking a vacation or away on business was simply not at home. It is, therefore, quite possible that a person who is in possession of a firearm, and who has, to the best of his own knowledge, both a licence and a registration certificate covering that firearm, may fall into violation of s. 91(1) as a result of revocation of his licence and/or registration certificate–without his knowledge. Again, CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) clearly “has the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong [emphasis added].”

- Similarly, prohibition orders against an individual may be issued by a provincial court judge who is proceeding ex parte [FA s. 75(4)]. It is quite possible that a person who has, to the best of his own knowledge, both a licence and a registration certificate covering his firearm may fall into violation of CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) as a result of issuance of such a prohibition order. Where such an order results in revocation of his licence and/or registration certificate [CC s. 116], that can quite possibly occur without his knowledge. Again, s. 91(1) clearly “has the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong [emphasis added].”

- 116. Every authorization, licence and registration certificate relating to any thing the possession of which is prohibited by a prohibition order and issued to a person against whom the prohibition order is made is, on the commencement of the prohibition order, revoked, or amended, as the case may be, to the extent of the prohibitions in the order.

Clearly, CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) is, in fact and in effect, “a law that has the potential to convict [and imprison] a person who has not really done anything wrong.”

CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112, therefore, “offends the principles of fundamental justice, and…such a law… violates a person’s right to liberty under s. 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.”

As support for that position, it is noteworthy that CC s. 92(1) is virtually identical in wording to s. 91(1). CC s. 92(1) exists, and it specifies another offence, in the form, “possesses a firearm…knowing that [he] is not the holder of (a) a licence…and (b) a registration certificate…[emphasis added]”

The reverse onus imposed by CC s. 117.11 does not apply to CC s. 92, 94, 95, or 97 offences.

Because s. 92(1) is specifically written to cover the situation where the accused knows that he or she is not the holder of the required licencing document, it follows that s. 91(1) and FA s. 112 are specifically designed to convict an accused who does not know that he does not have the required licensing document. The presence of CC s. 92(1) in the law, therefore, powerfully increases the potential for CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) to imprison an accused who has not really done anything wrong–by demonstrating Parliament’s intent that a person who lacks mens rea should be convicted.

If CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) is found to be an illegal provision, and a violation of section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, then CC s. 92(1) is a law that does not suffer from exactly the same defects. It will continue to be there, and continue to allow all prosecutions that are currently made under CC s. 91(1) or FA s. 112(1) to be made under CC s. 92(1).

A similar analysis of CC s. 92(1), however, may find that it, too, is unconstitutional.

CC s. 91(1) criminalizes possession of a firearm “unless the person is the holder of a licence.”

CC s. 92(1) criminalizes possession of a firearm by a person “knowing that the person is not the holder of a licence.”

CC s. 91(1) and 92(1) are both vulnerable to an attack based on price. It may be that a poor person cannot afford to pay the fee for a licence or a registration certificate, and therefore is criminalized by his or her poverty. If the only way a poor person can afford to buy a licence and a registration certificate is to sell his or her firearm to raise the necessary funds, is that reasonable?

The Supreme Court decided, in 1988, that offering, in the law, a defence document that is impossible to get is illegal.

The court ruled, in Morgentaler et al v. The Queen and the Attorney General of Canada (1988) 1 SCR 30:

- “Even if the purpose of legislation is unobjectionable, the administrative procedures created by law to bring that purpose into operation may produce unconstitutional effects and the legislation should then be struck down(emphasis added).” (62)

- “One of the basic tenets of our system of criminal justice is that when Parliament creates a defence to a criminal charge, the defence should not be illusory or so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory. The criminal law is a very special form of governmental regulation, for it seeks to express our society’s collective disapprobation of certain acts and omissions. When a defence is provided, especially a specifically-tailored defence to a particular [criminal] charge, it is because the legislator has determined that the disapprobation of society is not warranted when the conditions of the defence are met (emphasis added).” (70)

- “A further flaw with the administrative system established in [the Criminal Code] is the failure to provide an adequate standard for therapeutic abortion committees which must determine when [a document covering] a therapeutic abortion [i.e., a TAC] should, as a matter of law, be granted (emphasis added).” (68)

The precedent set by that case raises its head when a person is charged with possession of a firearm without a licence and/or without a registration certificate. The court ruled that ” when Parliament creates a defence to a criminal charge, the defence should not be illusory of so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory.”

If the person is charged with possession of a sawed-off shotgun without a licence and/or registration certificate, it must be noted that no licence or registration certificate covering such a firearm can be issued to any person other than a business with certain peculiar characteristics. For an individual, then, such a licence and/or registration certificate is most definitely “illusory, or so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory.”

If that defence created by Parliament is “illusory or so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory,” then the law says that the person can be sent to prison by that law even if the defence offered is “illusory of so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory.”

Once again, therefore, it appears that CC s. 91(1) has the potential to send a person to prison when the person has done nothing wrong. He or she is unable to avail himself or herself of the defence (the licence and/or the registration certificate created by Parliament and offered by the law as “a specifically-tailored defence to [this particular] criminal charge”) because the offered defence is “illusory, or so difficult to obtain as to be practically illusory.”

That defence has the potential to work for many charges under both CC s. 91 and s. 92.

CC s. 91(1) criminalizes possession of a firearm or other things “unless the person is the holder of a licence” (and a registration certificate, where applicable).

CC s. 92 criminalizes possession of a firearm or other things “knowing that the person is not the holder of a licence” (and a registration certificate, where applicable).

Licences covering firearms come in several types. The licences available as a result of FA ss. 12(2), (3), (4), (5), (6) and (7) are set so as to be unavailable to most individuals. The law does not indicate that the defences offered in FA s. 112(1), CC ss. 91(1), 91(2), 92(1), and 92(2) are not available to the majority of individuals and corporate persons; the defences, by implication of the wording of FA s. 112 and CC ss. 91 and 92, seem to be available to anyone who is charged.

CC s. 92(1) criminalizes possession of a firearm by a person “knowing that the person is not the holder of a licence.”

Therefore, the CC s. 91(1) offence may be committed when the person does not know that he or she is not “the holder of a licence.”

Under CC s. 117.04(2), for example, a peace officer (including “the reeve of a village” [CC s. 2 “peace officer” (a)]), may seize firearms without warrant.

If, for any reason, the “peace officer…is unable at the time of seizure to seize an authorization or a licence,” then “every authorization, licence and registration certificate held by the person is, as at the time of the seizure, revoked [CC s. 117.04(4)].”

It is therefore perfectly possible that a person’s licence and/or registration certificate can be revokedwithout his or her knowledge in those circumstances. He or she may be in illegal possession of a firearm with no knowledge that the licence in his or her wallet, and/or the registration certificate that he or she holds, has been revoked.

There are other provisions in firearms control law that also may cause a licence or registration certificate to be revoked in a way that leave the holder of that licence or registration certificate unaware of the revocation, and in possession of a firearm without a licence and/or certificate.

The registration certificate for a converted automatic [FA s. 12(3)] is “automatically revoked” if there is any “change of any alteration in the prohibited firearm that was described in the application for the registration certificate [FA s. 71(2)]. That charge can be triggered by the breaking of a defective weld, which was unknown to anyone. It might only be discovered much later, and it could give rise to a CC s. 91(1) charge.

In those circumstances, it is easy to see that any CC s. 91(1) or (2) or FA s. 112(1) charge is vulnerable to a constitutional (Charter) challenge.

A court may very well look favorably on such a challenge, because it leaves CC s. 92(1) and (2) (which are nearly identical) intact and ready for use.

CC s. 92(1) and (2) are much more difficult charges to prove, because the Crown must prove that the person is in the situation “knowingly.” The Crown must prove mens rea.

Importantly, the Crown does not have the advantage of the reverse onus provision in CC s. 117.11 for a CC s. 92, 94, 95, or 97 case.

Additionally, CC ss. 91(1) and 92(1) are both vulnerable to an attack based on price. It may be that a poor person cannot afford to pay the fee for a licence or a registration certificate, and therefore is criminalized by his or her poverty. If the only way a person can afford to buy a licence and a registration certificate is to sell his or her firearm to raise the necessary funds, is that reasonable?

A further problem arises when a licence or registration certificate expires. If the expiry passes unnoticed by the holder, then the person falls into violation of CC s. 91(1) or (2), but lacks mens rea. There was no intent to commit the crime. There was no actus reus, merely an oversight or lapse of attention to a detail that arises very seldom, and without warning.

Is it possible that a law can send a person to prison when there is no mens rea and no actus reus, merely because of an oversight?

Finally, there is the question of division of powers between the federal government and the provincial legislatures.

Frequently, an argument is made that conviction for a firearms control offence, under either the Criminal Code or the Firearms Act, does not require proof of mens rea because the offence is one against regulatory law. The Constitution divides the powers of government between the federal government and the provincial legislatures.

The federal government was, when the Constitution was adopted, given the authority to enact regulatory laws governing things (like aeroplanes) that did not exist in 1867. The authority to enact regulatory law regarding things that already existed in 1867 was assigned to the provincial legislatures.

Both the Firearms Act and Part II (the firearms sections) of the Criminal Code were enacted by Parliament under the authority given by the Constitution to Parliament to enact criminal law, and not under its very limited power to enact regulatory law.

Therefore an argument advanced by the Crown that any part of either the Firearms Act or Part III of the Criminal Code is, in any way, regulatory law, may render the section for which that argument is raised ultra vires (enacted in a way beyond the legal authority) of Parliament. Parliament has no authority to enact regulatory law regarding firearms, because firearms were available (unlike aeroplanes) in 1867. It can only enact criminal law in this area.

INSERT: This exercise is proceeding satisfactorily. Hundreds–perhapss even a few thousand–of 12(6) handgun owners have filed for their reference hearings. They will probably be successful–while those who complied with the instructions in the government’s bullying letters seem to have lost their chance of “grandfathering.”

Right now, the bureaucrats are regretting this gun grab. They’re, as usual, way over budget–and now they seem committed to confiscating little handguns at a cost of

between $3000 and $20,000 per handgun, the cost to government of fighting a reference hearing–at the FIRST level.The Conservatives are looking for a way around this problem, but right now the bureaucrats are stalled. Asking for a reference hearing puts everything on “hold.”

Nothing can happen until the reference hearing is completely over–even if it takes years and goes all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada. Once is is finally finished, then and only then does does the time (usually 30 days) that the owner was given to get rid of his or her little handgunbegin.To all of you who have asked for a referene hearing, I thank you, the NFA thanks you, and the recreational firearms community thanks you. Your courage and intelligence have stopped the Liberal gun grab in its tracks…with a little help from the NFA. The issues at stake have turned out to be far more complex and far more difficult to deal with than the bureaucrats expected.

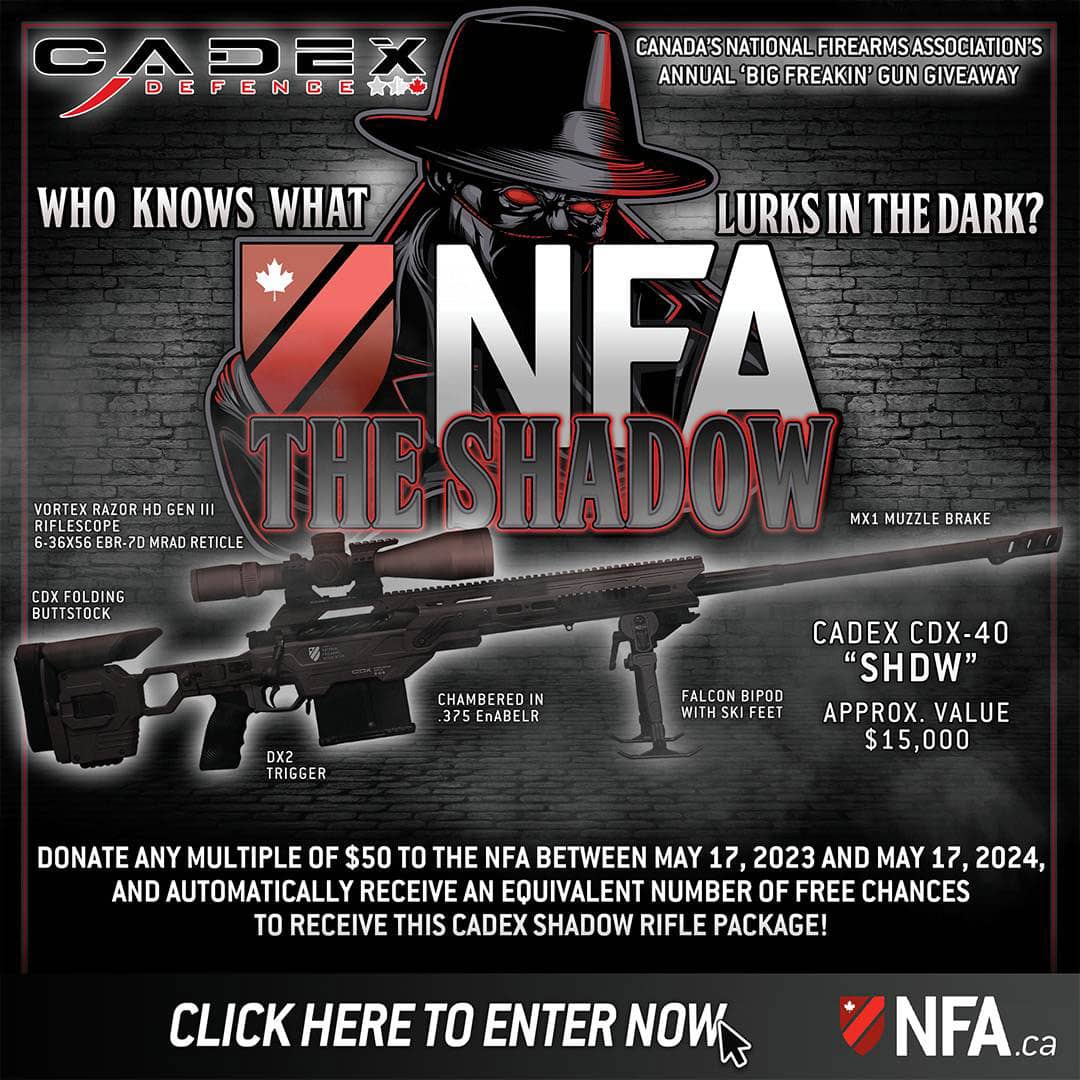

David A Tomlinson

National President

National Firearms Association

——————————————-> I plan on appealing the decision not to issue my registration for a prohibited firearm. Should I get a lawyer or can I handle the appeal myself?

Bill C-15, which became Bill C-10, which became Bill C-10A, was designed to legitimize two groups of FS s. 12(6) handguns– those in the possession of people like you, and those in the possession of firearms dealers. Bill C-10A was brought into force too late to help you, but it did legitimize the 12(6) handguns in the hands of dealers. Therefore, the effect of Bill C-10A was, in practice, discriminatory, contrary to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, section 15.

> Years ago we took your advice and bought a prohibited firearm (very cheap) in hopes of getting my wife grandfathered. Two friends did the same. Everyone signed a waiver saying they understood that these guns may be confiscated.

Those waivers were and are meaningless, they have no legal effect.

> She applied for a registration certificate, and received a green paper one, as the law required at that time. That certificate expired on 31 Dec 2002 as a result of the provisions of Firearms Act section 127(2)(b).

> > My friends have been received mail concerning the status of their guns. My wife has received nothing. Last week my friends got a registered letter telling them they had until the end of the year to dispose of the prohibited guns.

Those “final” letters were illegal. They were a refusal to issue a registration certificate, issued under the authority of Firearms Act section 72, but they did not conform to the requirements laid out in FA s. 72. For example, they did not contain “a copy of [Firearms Act] sections 74 to 81,” as required by law.

By sending those letters in that form, they apparently violated Criminal Code section 126 by doing something that “contravenes an Act of Parliament” by “willfully doing something omitting to do anything it requires.” That is an indictable offence, and the penalty is up to two years imprisonment.

What to do once a “final” letter has been received:

1. If you have access to someone who knows provincial court judges in your area, ask for the name of a judge who is friendly to firearms owners.

2. If you don’t, phone the provincial court house and ask for the name of a provincial court judge. DO NOT discuss why you want it, because that will set the clerk on a path of complex requirements that are NOT appropriate to this situation because this situation is different in the law to what the clerk is used to.

3. Write to the PCJ at the court house, saying:

(a) I have been refused a registration certificate by the attached (photocopy of) letter.

(b) I believe that this letter is illegal, because it does not conform to the law (FA s. 72).

(c) I believe that the writer violated Criminal Code section 126 when he sent me this, and I believe that if I do what he tells me to do, he will also be guilty of violating CC s. 380(1)(b) (the law against fraud). (Often, judges are bored by the endless stream of criminals in their courts. This complex mishmash of complicated legal issues gives them something they can get their teeth into.)

(d) I hereby refer this matter to you, personally, under FA s. 74(1) so that you, personally, may set up a reference hearing as required by FA s. 75(1).

By doing that, you force the firearms control bureaucrats to prepare for the reference hearing, which will cost them between $3000 and $20,000. It really is an expensive way to confiscate little handguns, but it is merely a citizen taking advantage of a right offered to him in the law. You apparently are able to choose which provincial court judge you would like to have hear the case, because the law is written so that you are offered that.

Additionally, it has another effect. You will be given “a reasonable period of time” to legally dispose of the little handgun. That period (no matter what the “final” letter says) “does not begin until after the reference is finally disposed of” [FA s. 72(6)].

Some people will fight the reference hearing with a lawyer, and may appeal the verdict to higher and higher courts. Some will fight it themselves, and may also appeal to higher courts. Some will fail to appear for it. Some are in one set of circumstances, some in another. It is not possible to cover all the possible variations here, so if you find this unclear, call (780)439-1394 (preferably between 8 and 11 AM, Alberta time) or send an email to

[email]dat@nfa.ca[/email]

But–regardless of how it is handled, or what the particular issues are, it will cost the firearms control bureaucrats $3000 to $20,000 out of their budget to prepare their case.

We didn’t write this defective law–they did.

David A Tomlinson

National President